The Secret History of the Moon and 37 Cents

Dateline: Florida Tech 1967

3 Men and a Woman Meet in a Bar …

The story is improbable. Three men and a single woman meet at a bar on A1A sometime in February 1958. One, a thirty something physicist, proposes the ridiculous idea of launching a college. Someone standing off to the side overhears the conversation and tosses thirty-seven cents of change from a long distance phone call on the bar and quips “go start your college with this.” No one knows precisely what the facts were. This is the legend.

Seven years later Jerry Keuper must have been thinking about this episode when he opened a letter from the advertising department of Time Magazine. In December 1966, Time announced a nationwide contest for a free, full page ad in the magazine. The magazine’s editors invited college and university presidents to submit one page descriptions of their schools. The most creative submissions would be published. Always on the look-out for ways to publicize Countdown College, Keuper summoned Homer Pyle, the college’s part time publicist, to his office. Pyle’s assignment: Come up with a proposal.

A few days later, Pyle returned with a draft for F.I.T.’s entry composed around a spoof on the title of W. Somerset Maugham 1919 novel The Moon and Sixpence. In Pyle’s parody, Maugham’s “Sixpence” became Keuper’s “37 cents” Keuper like the idea and submitted the copy. Weeks passed. Good news came in the form of a telegram from Time’s headquarters. ”The Moon and 37 Cents” was scheduled to be published in the magazine’s June 1967 Florida edition.

An Eventful Month

Time reached newsstands on Fridays. Each week Keuper and Pyle eagerly leafed through the weekly looking for the full page advertisement of Florida Institute of Technology. June 1967 proved to be a particularly newsworthy month. It made for interesting reading. The month began with the Beatles release of St. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. On June 5 the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War broke out in the Middle East. On June 12 the Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia voided the state’s prohibition of interracial marriages. Five days later China detonated its first hydrogen bomb. On June 20 after deliberating for only 20 minutes, a jury in Houston, Texas, convicted Muhammad Ali of draft evasion. The same day growing protests against the Vietnam War led the U.S. House of Representatives to pass a bill making the “burning of the American flag a federal crime.” Unfortunately, the bill’s authors left out the word “burning.” The U.S. Senate corrected the omission. The month ended with Barclay’s Bank in London introducing the first ATM on June 27 and NASA’s announcing that Major Robert H. Lawrence would be the first African-American astronaut. Six months later Lawrence would tragically die in a F-104 Starfighter training accident.

“The Moon and 37 Cents”

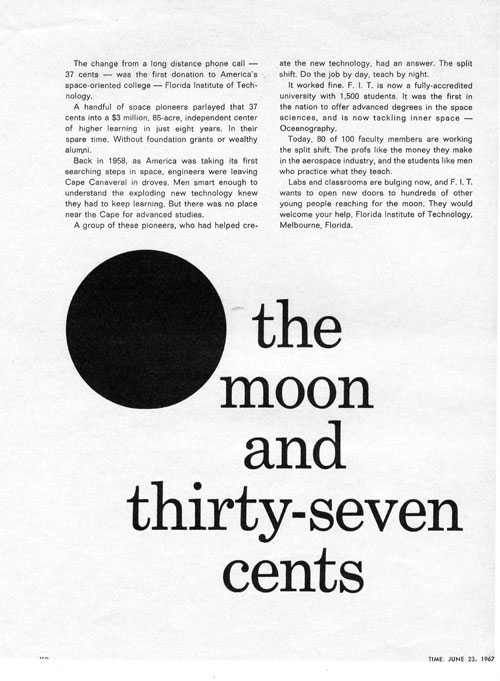

Countdown College’s “The Moon and 37 Cents” advertisement appeared in the June 23 Florida edition of Time Magazine on page X2. Copies of the magazine would reach 86,757 Florida households. The ad read:

The Moon and 37 Cents

The change from a long distance phone call — 37 cents — was the first donation to America’s space oriented college — Florida Institute of Technology.

A handful of space pioneers parlayed that 37 cents into a $3 million, 85-acre, independent center of higher learning in just eight years. In their spare time. Without foundation grants or wealthy alumni.

Back in 1958, as America was taking its first searching steps in space, engineers were leaving Cape Canaveral in droves. Men smart enough to understand the exploding new technology knew they had to keep learning. But there was no place near the Cape for advanced studies.

A group of these pioneers, who had helped create the new technology, had an answer. The split shift. Do the job day, teach at night.

It worked fine. F.I.T. is now a fully-accredited university with 1,500 students. It was the first in the nation to offer advanced degrees in space sciences, and is now tackling inner space — Oceanography.

Today, 80 of 100 faculty members are working the split shift. The profs like the money they make in the aerospace industry, and the students like the men who practice what they teach.

Labs and classrooms are bulging now, and F.I.T. wants to open new doors to hundreds of other young people reaching for the moon. They would welcome your help. Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida.

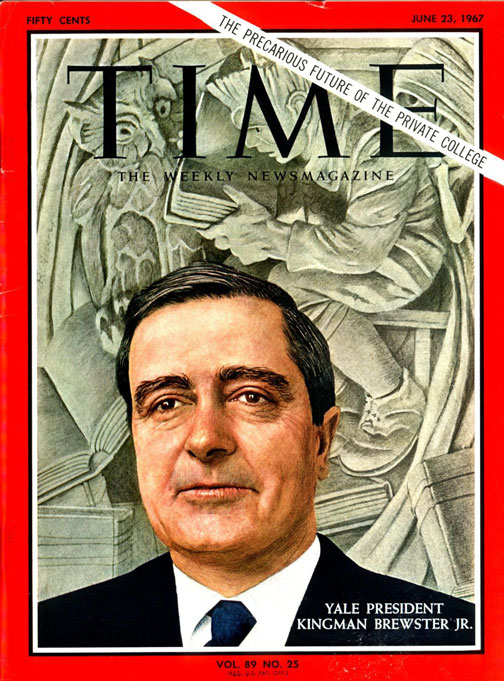

The June 23 issue of Time’s cover bore a picture of Yale’s President Kingman Brewster, Jr. with an accompanying sober storyline “The Precarious Future of the Private College.” The cover story chronicled the growing “anxiety behind the façade” of American private universities. The report painted a bleak picture. Faculty salaries were rising while the number of students was dwindling as the post war baby boom came to an end. The intensifying competition for students forced colleges and universities to launch massive fund drives “aimed at expanding facilities and adding new faculty.” Budgets were in the red. The future of private colleges and universities was uncertain. The article concluded that these schools “had their backs to the wall.” Some would survive, many more would fail.

Changing Times

Jerry Keuper must have chuckled when he read Time’s gloomy prognostications. He was confident that things were different at Countdown College. The students were serious. Enrollments were growing. In 1966 F.I.T. had 1541 students. A year later that number had climbed to 2118. All the trends pointed in the right direction. In the month before Time published “The Moon and 37 Cents” advertisement Eileen Hall, the university’s librarian, announced that the library had more than 20,000 books in its collection. Big plans were underway. Construction would soon start on a student union (Denius Student Center), a million dollar “science tower” (Crawford Building) and a radioactive Cobalt-60 test facility. No, Keuper must have thought as he scanned the Time cover story, things were different at FIT.

Keuper was wrong. At least that is what Harry Weber told him. Weber, who joined the faculty in 1966 was in charge of revamping the college’s science and engineering undergraduate curriculum, warned Keuper that the times were changing. Students in 1960s were different than the button down, seersucker suited students Keuper and John Miller had encountered at the University of Virginia in the early 1950s. He advised Keuper to scrap the college’s dress code in which students were told that “shorts, slacks, and pedal pushers are considered inappropriate for campus wear” and that “male students should shave daily.” Change was coming.

Harry Weber was right. As Countdown College entered its second decade, the older “Missilemen” who had formed the college’s core in 1958 were being replaced by a new generation of students. By 1967 a handful of women had enrolled in the rigorous science and engineering program. There were not many, but it was a beginning. Ethel Crews reported that when she walked to class, male students treated her like “something from another planet.” Carolyn Reagan, who was one of the university’s first African-American co-eds commented at the time “First you really have to prove yourself scholastically equal to the boys. Then, when you do, they resent it.” Reagan and her sisters’ message was simple: Get over it.

Other “changes” lay on the horizon. In September 1967 roughly 800 full-time students returned to campus. F.I.T. “Frogs”, freshmen and new students, received red and gray beanies and reminded that “beards and ‘beatnik’ hairdos are not acceptable at F.I.T.” Nearly two dozen students moved into the college’s first fraternity house (Alpha Kappa Pi). On October 15 Gleason Auditorium was opened to the public. A week later, four students were arrested in Countdown College’s first pot party. Keuper was shocked. First it was long hair. Now it was marijuana. Something had to be done. Keuper admonished students to act “like representatives of F.I.T.” and avoid conduct unbecoming future scientists and engineers. John Thomas, Melbourne’s police chief, acknowledged that there had been “rumors” of marijuana use at F.I.T. for several weeks. Thomas promised to track down the sources of the illicit drugs.

December brought the college’s first winter of student discontent when angry undergrads gathered in front of the president’s office (John Miller Office Building) protesting the cafeteria’s “deplorable food” and “bad living conditions.” This was the college’s first protest rally. Others would follow. The year ended with a round of protests triggered by the rumor that the administration planned to raise tuition from $30 to $35 dollars a credit hour. The proposed budget lifted the flat rate of tuition for a full load from $360 dollars a quarter to $420 bringing the annual tuition to $1260 (in 2018 $41,260) with the annual cost of room and board $885. “There’s going to be trouble,” a student shouted, “when they raise tuition.” Another expressed the students’ feelings succinctly: “Stop treating students like boys and girls and start treating us like men and women.”

Countdown College was growing up. The campus was adding new buildings. At the same time a new generation of faculty members like Andy Revay (recruited by Harry Weber) arrived in 1967. The next decade would see new programs in biology, science education, psychology, and the humanities. What remained constant at Countdown College was the gritty, can-do attitude that had first shown itself in the tavern on A1A.

The Stuff of Legends

“History is that certainty,” the protagonist in Julian Barnes’ novel The Sense of an Ending observed, “produced at the point where the imperfections of memory meet the inadequacies of documentation.” No one will ever know precisely what happened at the fabled bar in February 1958. The take-away may have been supplied in the parting dialogue in John Ford’s film The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence. The film opens with Jimmy Stewart, cast in the role of a U.S. Senator named Ransom Stoddard, returning with his wife to a frontier town to attend a rancher’s funeral. A journalist (call him a historian) asks why a senator would make such a long journey. What follows is a series of flashbacks in which Stewart reveals “who” really shot “Liberty Valence.” When he finishes his account, it is clear that Stoddard’s career was based on a fiction. The historian stands and rips up his notes. Stoddard asks, “You’re not going to use the story, Mr. Scott?” The historian responds, “This is the West, sir. When legend becomes fact, print the legend.” Perhaps this is all that needs to be said about “The Moon and 37 Cents.”

Note: F.I.T.’s Development Office is actively seeking information on the whereabouts of the family, friends, and descendants of the individual whose 37 cents launched the university’s first capital campaign. Small change, paper money, Bitcoin, etc. will be accepted. Time Magazine got it right: The future of private colleges is precarious.