The Secret History of Winning a $50 Million Grant

Florida Tech – 1997

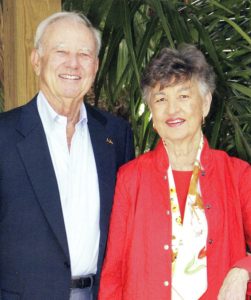

The stench from the red tide on the Indian River in late August 1984 was overpowering. Crossing the tarmac at the Melbourne airport, a Delta Airlines passenger named Anita Weaver was heard to exclaim to her husband, Lynn, “my God, what a smell.” Fighting back the urge to hold her nose, Anita Weaver added “I couldn’t live here!” The Weavers had arrived in Melbourne to watch the Space Shuttle Discovery’s maiden voyage. Weaver, dean of Auburn University’s Ginn College of Engineering, had been invited to the Kennedy Space Center (KSC) because of Auburn’s prominent role in the STS 41-D mission. Richard C. Smith, an Auburn graduate, was KSC’s director, and Henry “Hank” Hartsfield, another Auburn alumnus, was the Discovery’s commander. Discovery lifted off from KSC at 8:41 am on August 30, 1984, carrying a payload consisting of three communication satellites, an experimental solar array, an IMAX motion picture camera, and a collection of student experiments. Six days and fifty-six minutes later, STS 41-DTS, touched down on Runway 17 at Edwards Air Force Base in California. By then, the Weavers had returned home to a markedly less odiferous Alabama.

Three years later, in 1987, Lynn Edward Weaver returned to Melbourne to meet with the trustees of Florida Institute of Technology. Jerry Keuper’s announcement in 1985 of his retirement opened a two year presidential search. John Miller, who served for twenty years as Countdown College’s executive vice president, agreed to serve as the university’s second president while the Board of Trustees searched for a long-term successor. In August 1986, Florida Tech’s Board of Trustees announced that Donald Glower, dean of Ohio State’s College of Engineering (1976-1990), would become Countdown College’s third president. Two months later, a routine physical examination revealed health concerns which compelled Glower to withdraw his acceptance. Florida Tech’s trustees hastily formed a new presidential search committee. Six months later the college’s committee invited Lynn Weaver to come to Melbourne.

The meetings went well. Before leaving Melbourne, Weaver met privately with Jack Hartley, CEO of the Harris Corporation and an F.I.T. trustee. Hartley, who had served on Auburn’s faculty before joining Harris in 1956 , and Weaver had gotten to know one another after Weaver’s appointment as Auburn’s engineering dean in 1982. The men had a cordial, candid relationship. Weaver minced no words. He told Hartley that he would take the job if Hartley could assure him of Harris Corporation’s commitment to the university. A handshake followed. On June 22, 1987, Florida Institute of Technology announced that Lynn Weaver would become the university’s third president.

Countdown College had reached a turning point. Between 1980 and 1987 the university suffered a series of financial setbacks. Programs were cut; salaries frozen; the Jensen Beach campus closed; and, infrastructure needs were not addressed. Keuper’s decision in 1981 to acquire Nathaniel Hawthorne College had proved a disaster. In four years the New Hampshire based college had cost Florida Tech millions of dollars. The financial problems came to a head in 1985. Reluctantly, Jerry Keuper agreed that the time had come for him to step down as the college’s president. The university needed new blood at the top.

On Monday, August 10, 1987, Lynn Weaver arrived on campus. He radiated energy and determination. Weaver, who had not been given access to the university’s financial records during the interview process, was shocked as he scanned the college’s financial statement. His first order of business was to meet with Countdown College’s faculty and staff. He made clear his intention to bring radical changes in the university. “We will develop,” he revealed in an interview with an Orlando Sentinel reporter, “[a] the long –range plan while we’re planning the development campaign. I want to do this because I don’t want to wait. Time is important.” Weaver’s marching orders were clear. The university must wean itself from its reliance on student tuition. An endowment must be built. Funded research was essential. Within five years, Weaver promised, the university should double, no, triple its research grants and contracts. New buildings and laboratories were desperately needed. In the fall, Weaver announced the university would launch a capital campaign seeking donations from industry, alumni, and private individuals.

Behind the scenes, Weaver met with Jack Hartley and Bill Potter. Hartley and Potter, a prominent local attorney, led the effort to reconstitute the university’s board of trustees and mobilize support for the university. Bill Potter, Weaver recalled, was “a real asset to the university.” Whatever the job, Weaver added, Potter was always willing to take on the challenge. Jack Hartley’s support was critical. Within weeks of Weaver’s arrival, Hartley went to the Harris Corporation’s board of directors and secured the first of two five million dollar grants to Florida Tech. The challenges facing Countdown College, however, were formidable. The Harris Corporation’s generosity gave Weaver time to develop a long-range plan.

Lynn Weaver had no patience for persiflage. Born in 1930 in St. Louis, Weaver embodied the “Show-Me” state’s skepticism of fancy talkers and snake-oil salesmen. Weaver earned his B.S. in electrical engineering from the University of Missouri before serving in the Air Force as an electronics officer. After leaving the service, Weaver worked for McDonnell Douglas. Later he joined the B-36 strategic bomber and the highly classified X-6 experimental project at Convair Corporation. Work on the X-6, a proposed nuclear powered aircraft, took Weaver to Oakridge where he discovered his passion for nuclear engineering. During the middle 1950s, Weaver earned his master’s degree in EE from Southern Methodist University and went on to pursue his doctorate at Purdue in electrical engineering with a minor in nuclear physics.

In 1958, the newly minted Ph.D. joined the faculty of the University of Arizona (UA). The university had recently acquired General Atomics Triga reactor. Weaver had been in Tucson for only a few days before being summoned to Tom Martin’s office. Martin,UA’s dean of engineering, told Weaver that he knew next to nothing about nuclear reactors. “I want you,” Martin declared, “to take it [the reactor] over” and organize a nuclear engineering program. In an instant the twenty-nine year old became a full professor and department head. “I was,” Weaver observed, “in the right place at the right time.”

Weaver remained in Arizona until 1969 before accepting an appointment as the associate dean of the University of Oklahoma’s engineering college. Three years later Tom Stelson, Georgia Tech’s engineering dean, persuaded Weaver to move to Atlanta and become the director of the university’s School of Nuclear Engineering and Health Physics. Weaver remained at Georgia Tech for a decade before being recruited by Auburn to become the university’s engineering dean.

Weaver was a talented administrator. The presidency of Countdown College offered Weaver a marvelous opportunity to prove his mettle. “I don’t think I’m smart enough to make a difference in science and technology,” Weaver observed years after coming to Melbourne. But,” Weaver paused to add emphasis, “I can apply my skills to building an institution.” Florida Tech offered him the chance to become an agent of change. He set himself the goal of making F.I.T. one of the premier scientific and technological universities in the Southeast.

Money was the problem. There was never enough. The Harris Corporation’s 1987 five million dollar gift gave Weaver time to develop a long-range plan. Shortly after his arrival, he hired a Dallas consulting company to help formulate a capital campaign. The Texans told him that he would be lucky to raise six million dollars. Weaver discounted their advice and set a goal of twenty-five million dollars. When completed, the campaign raised twenty-six million.

Despite his success in his first foray into fund raising, problems grew. Weaver persuaded one of his former students, Allan Mense, who served as the acting chief scientist for the Reagan administration’s Strategic Defense Initiative (Star Wars), to serve as Countdown College’s vice president for research. Mense angered many established members of the faculty with his abrasive tone and what most considered unrealistic goals.

While the faculty grumbled about vice-president Mense, Lynn Weaver had quietly begun to cultivate a relationship with the directors of the F.W. Olin Foundation. In 1990, Weaver submitted a proposal to the Olin Foundation for a new engineering building. F.I.T. was one of the three finalists. The Olin Foundation gave the university a $100,000 consolation prize. When Weaver asked for an explanation for why the application had not been approved, the Olin Foundation’s directors told Weaver they were not sure that Countdown College would survive. “You may not,” they explained, “be around. That’s why you [F.I.T.] did not get the grant.”

Discontent grew. Morale plummeted when it was learned that the university was running a deficit. Rumors of possible lay-offs swept across campus in May 1991. In June, Tom Adams, Jerry Keuper’s friend and the university’s vice president for development, launched a carefully planned coup d’état against Weaver. Claiming to represent an anonymous “University Survey Committee,” Adams mailed a “survey” to Countdown College’s 630 faculty members. “There are a lot of people who have worked hard at F.I.T. and now” Adams told an Orlando Sentinel reporter in a thinly veiled reference to Lynn Weaver, “in the last three years; it’s on the verge of going down the tubes.” The seventy-four year old Adams, whose position was scheduled to be eliminated on June 30, asserted that a sizeable number of the university’s trustees and faculty had lost confidence in Weaver. The politically savvy Adams had misjudged the situation. The attempt to unseat Weaver ended in Adams’ dismissal. Confidence in Weaver’s leadership, however, was shaken.

Weaver remained resolute. Tenacity was his strong point. In the next three years, he kept in contact with the Olin Foundation. By 1994, Weaver was ready to submit a second application to Foundation. This time he sought funding for a biology building. A few days after mailing in the proposal, Larry Milas, the Foundation’s lead director, phoned Weaver asking if he” had any plans to be in New York anytime soon.” “No,” Weaver answered, “but I can be in New York whenever you want.” Milas said that was not necessary. He would be in Florida in a few weeks visiting his vacation home on Longboat Key. Perhaps, Milas added, Weaver could meet him there. Weaver countered with an invitation for Larry Milas and his wife to come to dinner at the Weaver’s house on Merritt Island. “Anita,” Weaver added, “is a good cook.” Milas agreed, telling Weaver that their meeting must remain strictly confidential.

Weaver invited Jack Hartley and his wife, Martha, to join the dinner party. Milas arrived with his wife and William Schmidt, one of the other Olin directors, who was accompanied by his wife. The evening went well. Weaver had not exaggerated. Anita Weaver had prepared a marvelous meal featuring a succulent tenderloin. After dinner the three couples adjourned to the Weaver’s porch. It was a lovely January night. A gentle breeze wafted across the Banana Rive as the moon rose over the horizon. Weaver poured another round of drinks. Out of the blue Larry Milas asked: “What would you do if you had some money?” Weaver answered with a question, “How much?” Milas paused, as if picking a figure out of the air, and answered “say, a $100 million.” Then, almost as if it had only then occurred to him, Milas added “would you put a proposal together?” A few minutes later the Milases and Schmidts left for their hotel. As their car pulled away a wide-eyed Weaver looked at Hartley and asked, “Jack, did you hear the same thing that I did?” The next day Weaver set to work formulating what would grow to a $125 million proposal for the Olin Foundatio

At the time, Weaver was unaware of two things. First, the Olin Foundation directors had decided to go out of business. Second, the four directors were divided in what they wished to do with the foundation’s assets. Larry Milas wanted the money to go towards creating a new engineering college that would be associated with Babson College in Boston. Milas was a Babson alumnus and one of college’s trustees. Two directors of the foundation’s directors disagreed. They were impressed with Weaver’s vision and determination. They became Countdown College’s advocates.

Two years of proposals and counterproposals ensued. Weaver’s quiet resolve and patience paid off. In June 1997 the Olin Foundation announced their decision to award Florida Institute of Technology a $50 million dollar grant. The Olin Foundation described Countdown College as “a diamond in the rough.” “We identified the school,” Larry Milas explained, “as a center of academic excellence. As we looked recently at our grant objectives, it seemed the most outstanding nationally for this grant. It’s the largest gift the foundation has bestowed.”* $50 million dollars would go a long way in polishing the stone.

Securing the gift was a momentous first step. Much work, however, remained. The terms of the agreement required the Olin Foundation’s approval of the grant’s utilization. The stipulation that the contracts for the Olin Engineering Complex and the Olin Life Sciences Building must be awarded to the lowest bidder produced numerous problems. Lynn Weaver, who retired as Florida Tech’s third president in 2002, devoted the next five years organizing the transformation of what had begun as a night-time, after-work college for “Missilemen” into a world-class university. Ever modest, Lynn Weaver gave credit to the trustees, faculty, students, and alumni for his accomplishments.

Postscript:

Kenneth Burke (1897-1993), the American philosopher and literary critic, described overhearing a heated discussion between Lincoln Steffens (a well-known American journalist 1866-1936) and a friend walking down 42nd Street in New York City. This fanciful exchange bears some relevance to Countdown College’s relationship with the Olin Foundation. In Burke’s imaginary conversation, Steffens’ friend announced that he had formulated a plan “that would resolve all of humanity’s outstanding problems.” As the men turned onto Fifth Avenue, Steffens noticed a stranger who was following them.

“You seem interested in my friend’s plan,” Steffens observed.

The stranger, who was in fact, the Devil, responded “Decidedly!”

Steffens: “What do you think of it?”

The Devil: “I think it is an excellent plan.”

Steffens: “You mean to say you think it would work?”

The Devil: “Oh, yes. It would certainly work.”

Steffens: “But in that case, how about you? Wouldn’t you be out of a job?”

The Devil: “Not in the least. I’ll organize it.”

As with all things concerning human affairs in general and the history of Countdown College in particular, Lynn Weaver would, I think, agree — the devil lies in the details.

*The Olin Foundation Grant came with a long list of stipulations covering the dispersal of the funds. $25 million would come as a direct cash gift. The second $25 million would be released on a dollar for dollar match for funds raised by the university. Funds from the initial $25 million went to the construction of the Olin Engineering Complex and the Olin Life Sciences Building. The Olin Foundation maintained a close oversight of the details of the buildings’ construction. The Olin Foundation provided additional funds outside the original grant for the completion of the Charles and Ruth Clemente Center for Sports and Recreation and in 2005 a matching grant for the F.W. Olin Physical Science Center.

Note: Matthew Ruane, Florida Tech professor and winner of the 2018 Kerry Clark Faculty Excellence Award for Teaching, has written an insightful account of the complex, nuanced story of the Olin Foundation’s relationship with Countdown College in his 2014 dissertation: Transforming a University? A Qualitative Analysis of the Grantee-Grantor Relationship Between Florida Institute of Technology and the F.W. Olin Foundation.