Did Gravitational Waves Knock a Huge Black Hole From the Center of its Galaxy?

Team of Hubble Telescope data analysts, including Florida Tech’s Eric Pearlman, helped make the potential discovery

Astronomers have uncovered a supermassive black hole booted from the center of a distant galaxy by what could be the awesome power of gravitational waves.

Though there have been several other suspected, similarly booted black holes elsewhere, none has been confirmed so far. Astronomers think this object, detected by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope, is a very strong case. Weighing more than 1 billion suns, the rogue black hole is the most massive black hole ever detected to have been kicked out of its central home.

Researchers estimate that it took the equivalent energy of 100 million supernovas exploding simultaneously to jettison the black hole. The most plausible explanation for this propulsive energy is that the monster object was kicked by gravitational waves unleashed by the merger of two hefty black holes at the center of the host galaxy.

First predicted by Albert Einstein, gravitational waves are ripples in space that are created when two massive objects collide. The ripples are similar to the concentric circles produced when a rock is thrown into a pond. Last year, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) helped astronomers prove that gravitational waves exist by detecting them emanating from the union of two stellar mass black holes, which are several times more massive than the sun.

“We’ve known for many years that most galaxies have supermassive black holes, but most of them aren’t active or accreting much matter–like the one in the center of the Milky Way” said Florida Tech astrophysicist Eric Pearlman, who was a part of the team that analyzed the data from the Hubble Telescope. “Models suggest that what turns on the activity for black holes is an influx of material, probably caused by a galactic ‘train wreck’: two galaxies running into one another and merging. The merger of black holes that would result from this could also produce exactly the kind of kick we think happened to knock this black hole out of the host galaxy’s center. This is the first time that we’ve seen the pieces fall into place so well to support this model.”

Hubble’s observations of the wayward black hole surprised the research team. “When I first saw this, I thought we were seeing something very peculiar,” said team leader Marco Chiaberge of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) and Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Maryland. “When we combined observations from Hubble, the Chandra X-ray Observatory, and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, it all pointed towards the same scenario. The amount of data we collected, from X-rays to ultraviolet to near-infrared light, is definitely larger than for any of the other candidate rogue black holes.”

You can read Chiaberge’s paper in Astronomy & Astrophysics here.

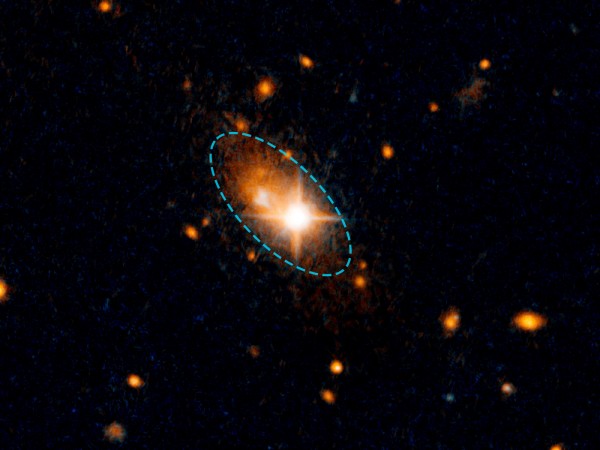

Hubble images taken in visible and near-infrared light provided the first clue that the galaxy was unusual. The images revealed a bright quasar, the energetic signature of a black hole, residing far from the galactic core. Black holes cannot be observed directly, but they are the energy source at the heart of quasars – intense, compact gushers of radiation that can outshine an entire galaxy. The quasar, named 3C 186, and its host galaxy reside 8 billion light-years away in a galaxy cluster. The team discovered the galaxy’s peculiar features while conducting a Hubble survey of distant galaxies unleashing powerful blasts of radiation in the throes of galaxy mergers.

Based on this visible evidence, along with theoretical work, the researchers developed a scenario to describe how the behemoth black hole could be expelled from its central home. According to their theory, two galaxies merge, and their black holes settle into the center of the newly formed elliptical galaxy. As the black holes whirl around each other, gravity waves are flung out like water from a lawn sprinkler. The hefty objects move closer to each other over time as they radiate away gravitational energy. If the two black holes do not have the same mass and rotation rate, they emit gravitational waves more strongly along one direction. When the two black holes collide, they stop producing gravitational waves. The newly merged black hole then recoils in the opposite direction of the strongest gravitational waves and shoots off like a rocket.

The researchers are lucky to have caught this unique event because not every black-hole merger produces imbalanced gravitational waves that propel a black hole in the opposite direction. “This asymmetry depends on properties such as the mass and the relative orientation of the back holes’ rotation axes before the merger,” said team member Colin Norman of STScI and Johns Hopkins University. “That’s why these objects are so rare.”

An alternative explanation for the offset quasar, although unlikely, proposes that the bright object does not reside within the galaxy. Instead, the quasar is located behind the galaxy, but the Hubble image gives the illusion that it is at the same distance as the galaxy. If this were the case, the researchers should have detected a galaxy in the background hosting the quasar.

If the researchers’ interpretation is correct, the observations may provide strong evidence that supermassive black holes can actually merge. Astronomers have evidence of black-hole collisions for stellar-mass black holes, but the process regulating supermassive black holes is more complex and not completely understood.

The team hopes to use Hubble again, in combination with other facilities, to more accurately measure the speed of the black hole and its gas disk, which may yield more insight into the nature of this bizarre object.

(Thanks to Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Maryland for providing text)

%CODE1DISCOVERYMAGVOL13%