University Shark Expert Answers: Why Are Shark Attacks So Rare?

By Toby Daly-Engel

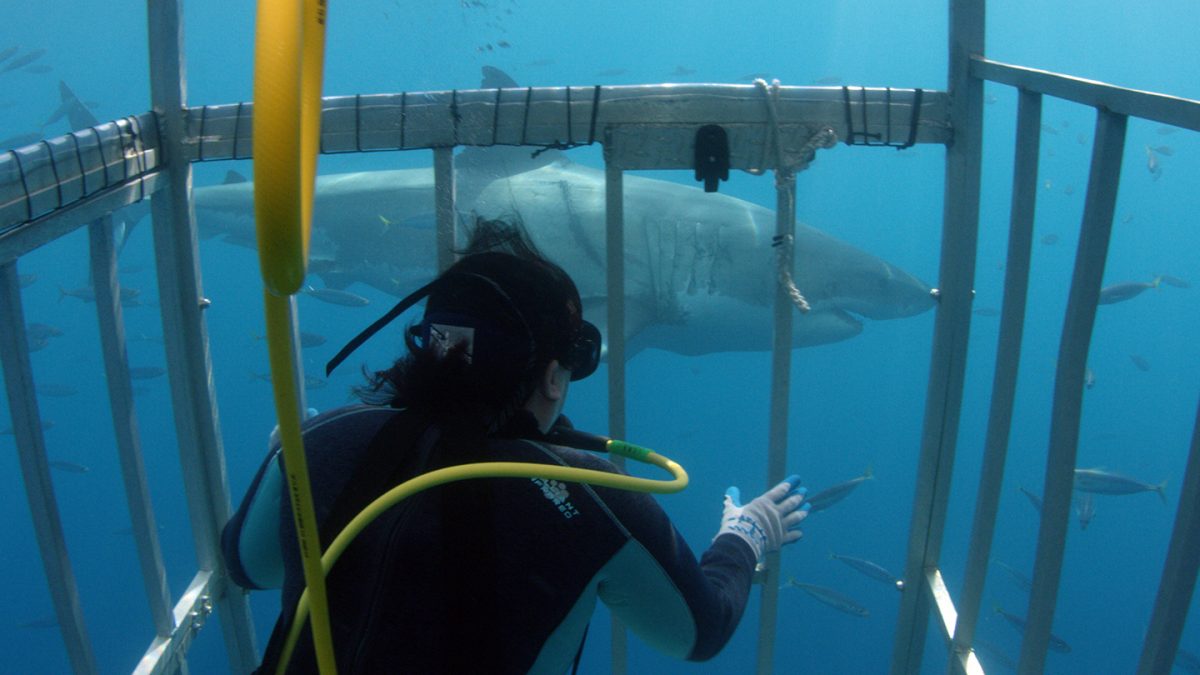

Toby Daly-Engel tagging a small blacktip shark during a tagging program she ran in Pensacola, Florida. Credit: Jeff Eble.

You are more likely to be killed by a Christmas tree, a vending machine or a toilet bowl than you are a shark.

But if you only listened to the annual headlines about sharks appearing perilously close to shore, waiting to prey indiscriminately on native Floridians and snowbirds alike, or watched movies that cast sharks as voracious, mindless killers, you might think that sharks eat humans all the time—or at least, they want to.

The reality, however, is far different.

Sharks and their relatives are the top predators in nearly every aquatic environment on the planet. They have six finely honed senses, including their famous talent for smelling blood in the water, an even better sense of hearing and the incredible ability to detect small electrical impulses emitted by hidden prey.

Sharks can eat just about anything the ocean has to offer, including loud, splashy, easy-to-find humans invading their territory. In short, if sharks wanted to eat us, they absolutely could.

However, only about 50 attacks occur per year in the U.S., and fewer than 3% result in death.

Why so few?

First, sharks are hardly the mindless feeding machines that Hollywood makes them out to be. They live as long as, or even longer than, humans—and you do not get to live that long by being reckless.

Sharks are naturally cautious creatures. Because their natural prey are mostly fish, marine mammals and sea turtles—which have sharp spines, claws and beaks that can inflict a lot of damage during a predation event—sharks prefer to scavenge injured or dead food over chasing healthy prey that can fight back. Also, they are not hunger-driven, meaning a shark that has starved for a week is no more likely to attack than a shark that ate an hour ago.

Second, and most important, humans are air-breathing, terrestrial animals, not aquatic, so not a shark’s natural prey. Since we don’t resemble their usual food, we may be a threat, and sharks tend to avoid us.

Why, then, do sharks attack humans at all?

Nearly half of all documented shark attacks are actually provoked by humans. The others, it is thought, result from mistaken identity: To a shark, a person splashing around may look like a tasty—and perhaps injured—seal.

If you are in the water and see a shark, my advice is to move slowly and calmly and avoid splashing.

But when it comes to surviving those toilet bowls, you’re on your own.

Toby Daly-Engel is director of Florida Tech’s Shark Conservation Lab and an assistant professor of ocean engineering and marine sciences who uses molecular tools and fishery-independent monitoring to research how shark populations are responding to climate change. This work is supported by private donations; contribute at give.fit.edu/shark.

This story was featured in the spring 2020 edition of Florida Tech Magazine. Read the full issue here.