The Secret History of the Naked Streak

Dateline: Florida Tech 1974

The two naked men were moving fast when they passed in front of the Denius Student Union on Tuesday, March 5, 1974. One had a towel wrapped around his head; the other wore a Groucho Marx mask and a backpack. A student wondered as “Groucho” passed “why the back-pack.” Perhaps it was because finals were approaching. At Countdown College even buck-naked students were serious about their studies. “It was,” Doug Zinn, a freshman living in Wood Hall declared, “a good streak. They [sic] were making a good pace.” Two hours later a third streaker dashed from Wood Cafeteria to Shaw Hall. The next day a reporter quizzed Dale Simcox, F.I.T.’s facilities superintendent who bore responsibility for campus security, for details on what was Brevard County’s first streak. “There is no report,” Simcox answered, “of that whatsoever…That wouldn’t happen here.” The next seventy-two hours would prove Simcox wrong. The national “streaking” craze had come to Florida Institute of Technology.

The history of American college students dashing in the nude dates from the early 19th century. In 1804, George Crump, a student at Washington College and later a U.S. Congressman, removed his clothes and ran through Lexington, Virginia, before being apprehended by the local police. Sixty years later Robert E. Lee, who served as the college’s eleventh president made it known that he considered such promenades a right-of-passage. “We have one rule here,” Lee explained, “and it is that every student be a gentleman.” The former Confederate General found no contradiction between being a “gentleman” and his students’ proclivity to saunter forth unclothed.

The history of American college students dashing in the nude dates from the early 19th century. In 1804, George Crump, a student at Washington College and later a U.S. Congressman, removed his clothes and ran through Lexington, Virginia, before being apprehended by the local police. Sixty years later Robert E. Lee, who served as the college’s eleventh president made it known that he considered such promenades a right-of-passage. “We have one rule here,” Lee explained, “and it is that every student be a gentleman.” The former Confederate General found no contradiction between being a “gentleman” and his students’ proclivity to saunter forth unclothed.

A century later the fad of students running naked through public places swept across college campuses. The modern usage of the word “streaking” was coined in 1973 when a Newsweek Magazine reporter observed a group of University of Maryland naked students “streaking past him right now.” A year later streaking fever raged on college campuses. Students at Countdown College were determined not to be left behind.

Within hours of the Denius Student Union “incident” a whispering campaign began rallying support for a mass campus streak. The plan was for students to gather at the Crawford Science Building at 10:00 pm on Thursday, March 7. The university’s response was muted. John Miller, academic vice president, considered it a harmless lark. “I think,” Miller chortled, “that everyone will treat it as a joke…We’re no different than any other university in that respect and these fads come and go.” Robert Cotron, Melbourne’s Chief of Police, agreed saying that the police had no intention of getting involved. “If the school doesn’t care,” he explained to a newspaper reporter, “we don’t care.” Behind the scenes a handful of Countdown College’s professors quietly supported the students. One professor under the veil of anonymity said that he would take part if he wouldn’t get fired. Another observed that if Countdown College did not have a football team at least students could be part of a “streaking team.”

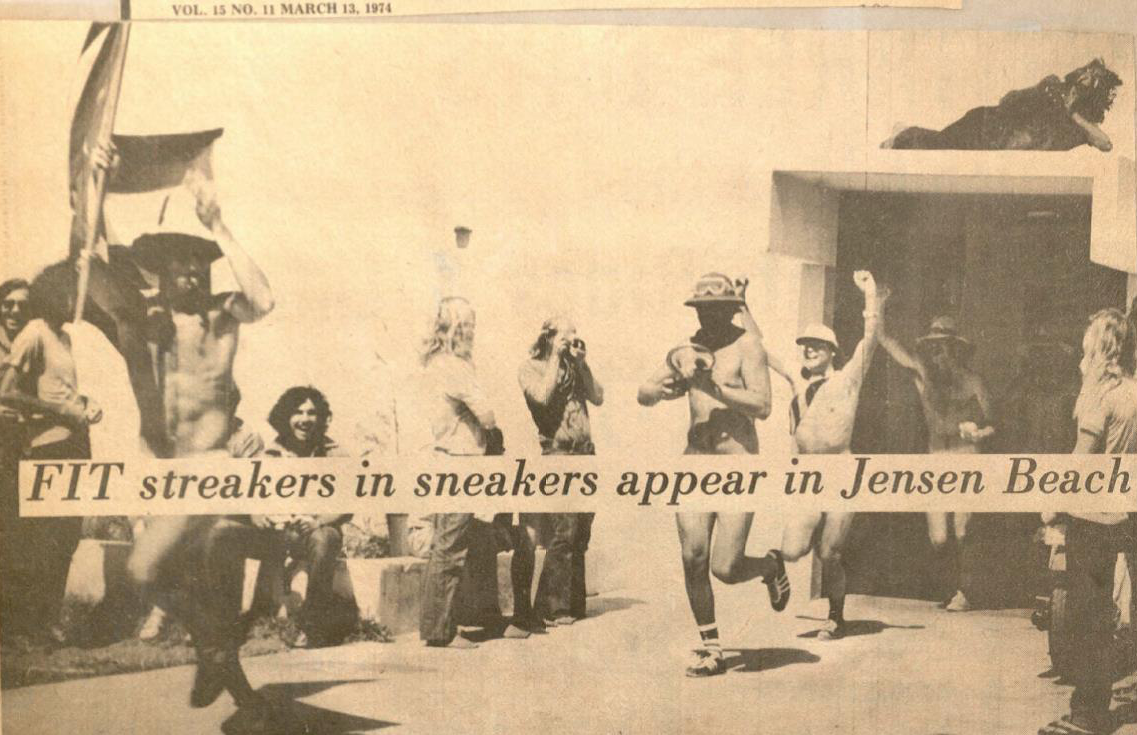

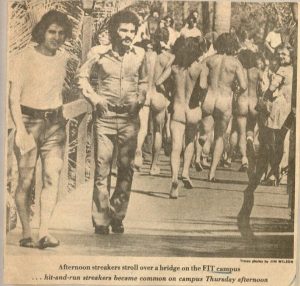

Excitement grew as news of the planned streak was reported by the local press. Sporadic streaks took place on the Melbourne and Jensen Beach campuses on Wednesday and Thursday in the hours leading up to the mass streak. Late on Thursday afternoon more than 50 Jensen Beach students arrived to lend their support to their Melbourne brethren. One professor recalled that he was surprised how many of his students showed up for early evening classes wearing raincoats. It had rained earlier in the day. The rain, however, had stopped. Even more curious, the professor noted, was that the students declined to remove their raincoats for the entire class period. By nine o’clock a crowd of nearly 1,000 people had gathered. Police Chief Cotron ordered 15 police officers to maintain a perimeter along Country Club Drive to insure the streakers remained on course.

Excitement grew as news of the planned streak was reported by the local press. Sporadic streaks took place on the Melbourne and Jensen Beach campuses on Wednesday and Thursday in the hours leading up to the mass streak. Late on Thursday afternoon more than 50 Jensen Beach students arrived to lend their support to their Melbourne brethren. One professor recalled that he was surprised how many of his students showed up for early evening classes wearing raincoats. It had rained earlier in the day. The rain, however, had stopped. Even more curious, the professor noted, was that the students declined to remove their raincoats for the entire class period. By nine o’clock a crowd of nearly 1,000 people had gathered. Police Chief Cotron ordered 15 police officers to maintain a perimeter along Country Club Drive to insure the streakers remained on course.

At ten o’clock a bugle sounded and close to six hundred students, who had gathered at the Crawford Science Building, removed their raincoats and broke into a run. Shouting “We’re Number One” the naked throng raced past the president’s office through the dorm quad and on to Roberts Hall. Some of the students sported bow ties as a salute to Jerry Keuper who always wore a bow tie. Others displayed their filiality by carrying signs saying “Hi Mom” and “Hi Pop.” One of the estimated fifteen co-eds who joined in the sprint wore bunny ears. A male student followed wearing a sombrero. A team of naked streakers pulled a chariot. One streaker rode a bicycle while another arrived on a motorcycle. The streak was over in a matter of minutes. It was estimated that 55% of F.I.T.’s student body had participated in the streak. By midnight the Jensen Beach streakers were on their way home, and the Melbourne students were back in their dorm rooms.

At ten o’clock a bugle sounded and close to six hundred students, who had gathered at the Crawford Science Building, removed their raincoats and broke into a run. Shouting “We’re Number One” the naked throng raced past the president’s office through the dorm quad and on to Roberts Hall. Some of the students sported bow ties as a salute to Jerry Keuper who always wore a bow tie. Others displayed their filiality by carrying signs saying “Hi Mom” and “Hi Pop.” One of the estimated fifteen co-eds who joined in the sprint wore bunny ears. A male student followed wearing a sombrero. A team of naked streakers pulled a chariot. One streaker rode a bicycle while another arrived on a motorcycle. The streak was over in a matter of minutes. It was estimated that 55% of F.I.T.’s student body had participated in the streak. By midnight the Jensen Beach streakers were on their way home, and the Melbourne students were back in their dorm rooms.

A backlash against the night’s “lamentable happenings” at Countdown College grew in the two weeks following the streak. One middle-aged resident who was a member of the 1,000 spectators who lined Country Club Drive complained of the students’ “disgusting” behavior. Two Melbourne city councilmen protested the city’s inaction. The complaints led Police Chief Cotron to reconsider his initial unwillingness to take action. “It is neglect of duty,” Cotron declared, “if we don’t do something.” Cotron told reporters that he had contacted Abbot Herring, the state attorney, and requested his office to issue “John Doe” warrants for the streak’s participants. Harry Stein, the chief attorney in Herring’s office assigned to the case promised “we’ll do what’s necessary after we see what we get from the police.”

Chief Cotron believed that indictments were imminent. During the streak his deputies had confiscated a roll of film containing pictures of the streakers from a student photographer for the Crimson. “We got between 50 and 70 pictures,” Cotron told an Orlando Sentinel Star reporter. “I’ve assigned two, two-man teams to go to FIT,” he added, “and try to identify as many of the streakers as possible. Then I’m going to turn it all over to the state attorney, and he can do what he wants to do.” Nothing came from the Melbourne detectives’ suggestion that the school should post the pictures on school bulletin board and invite parents to come and identify their wayward children.

Edward Thompson, pastor of the First Assembly of God and head of the Brevard Ministerial Association, led the charge calling for action against the streakers. In a letter to Jerry Keuper, Thompson accused Countdown College’s administration with fostering a “permissive attitude” that encouraged the student’s errant behavior. “Many persons,” Thompson declared, “have chosen Melbourne as their residence because of its high spiritual and moral standards.” Thompson demanded Keuper “make every effort to not only maintain but strengthen the moral, social, and cultural environment.” Keuper did not reply.

Edward Thompson, pastor of the First Assembly of God and head of the Brevard Ministerial Association, led the charge calling for action against the streakers. In a letter to Jerry Keuper, Thompson accused Countdown College’s administration with fostering a “permissive attitude” that encouraged the student’s errant behavior. “Many persons,” Thompson declared, “have chosen Melbourne as their residence because of its high spiritual and moral standards.” Thompson demanded Keuper “make every effort to not only maintain but strengthen the moral, social, and cultural environment.” Keuper did not reply.

The police’s confiscation of the student photographer’s film provoked outrage on campus. Citing the Bill of Right guarantee of the freedom of the press, Kerry Clark, a respected member of the university’s biology department, demanded that the photographs be returned to the Crimson. The film was returned and the idea of displaying the photographs on a campus bulletin board was dropped. No legal action was taken against any of the streak’s participants.

Pastor Thompson responded with a call for prayer. “God himself was first to clothe man,” Thompson declared. “Man’s need to wear clothes dates from the Garden of Eden…Since God was the first one to clothe man in public, man should therefore heed this. Undressing is reserved for the private places between a husband and wife.” Countdown College’s faculty and students must repent. “Some people,” Thompson declared in a pointed reference to F.I.T.’s administration, “take this streaking lightly, as funny or a joke. Disobedience to God’s commands is not a joke. It is evidence of a sick society.”

Not all religious authorities shared Thompson’s concerns. A reporter for the Disciples of Christ’s magazine The Christian Century characterized streaking as a bold existentialist statement. Streaking was described as an instance of “Kierkegaard’s leap of faith.” Students who removed their clothes were demonstrating “the courage to be.” The theological debate remained unsettled. In Melbourne, F.I.T. students returned to their books to prepare for finals. The streaking fad ended.

The polyester 1970s were rich in eccentricities. This decade brought us 8-Track tape players, EST therapy, platform shoes, disco, and the mantra “do your own thing.” It was also a decade that brought profound change. This was a decade that began with the Beatles’ breakup and ended with a nation locked in the throes of hyper-inflation. In the intervening years Americans endured the OPEC oil embargo, Watergate, the fall of Saigon, the Iran hostage crisis, and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In retrospect, the great Florida Tech streak is a reminder of a gentler, “laid back”, moment in a turbulent era. John Miller was right. Fads come and go. Streaking at Florida Tech was superseded in 1975 when students adopted the decade’s next craze: pet rocks.

| Documentation for the Secret History series comes from the Keuper Scrapbooks, photograph collection, and university papers in the Harry P. Weber University Archives or Florida Institute of Technology Special Collections, John H. Evans Library, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, FL. |