The Secret History of Launching Florida Tech

Dateline: Florida Tech 1958

East central Florida underwent a revolution in the 1950’s. The sleepy, fishing communities stretching from Titusville to Melbourne along the Atlantic Coast began to receive an influx of engineers, scientists and technicians. In 1948 the first wave of “Missilemen”* arrived. An army of 75,000 technicians, engineers and scientists followed in the next ten years. 1958 was a year of change. In January, the United States launched its first satellite into orbit. In July, President Eisenhower signed into law the bill creating NASA. A month later the Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) called for the creation of a new super-rocket code-named Saturn. Less attention was given to a young RCA physicist’s announcement in May of the creation of Brevard Engineering Institute (BEI). When classes began in September the school’s name had changed to Brevard Engineering College (BEC). Eight years later in 1966, Florida’s Secretary of State approved BEC’s request to change its name to Florida Institute of Technology.

Russians Win Race to Launch Earth Satellite

The Soviet launch of Sputnik on 4 October 1957 sparked a heated debate in America and around the world. Within a month the Russians had a second Sputnik, weighing 1100 pounds and carrying a barking dog named Laika, in orbit. On December 6, 1958, the United States first effort to launch a four-pound satellite into orbit ended with an explosion on the launch pad. The next day London Daily Express ran the banner headline “U.S. Calls it Kaputnik.” Edward Teller warned that the US faced “technological Pearl Harbor.” In the twelve years since the end of World War II, American science and technology had lost its preeminent position. Commentators blamed American education. Thousands rushed to by a book which had appeared in 1955 entitled Why Johnny Can’t Read. Harvard’s President, Nathan Pusey, called for a higher percentage of the nation’s gross national product to be spent on education.

On January 31, 1958, 119 days after Sputnik’s launch, Explorer 1, America’s first satellite, lifted into orbit. Putting a satellite in orbit was only the beginning. The long-term success of America’s space program rested on the shoulders of the nation’s scientists and engineers. There were, however, disturbing trends. In 1958, the Engineering Manpower Commission reported that “freshman engineering registrations dropped 11 percent” against an over-all 7 percent increase in college enrollments. Fewer and fewer young people were choosing science and engineering as their majors in college. Perhaps worse still, the scientists, engineers, and technicians at the Cape lacked an opportunity to advance their education.

Keuper Leaves the Snow of the Northeast for Sunny Florida

Jerry Keuper had just crossed Florida state line driving a station wagon towing his 1952 MG when he heard Maj. Gen. John B. Medaris, commander of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA), announce the successful launch of Explorer I. Keuper, his wife Natalie and their infant daughter Melanie were on their way to Melbourne, Florida where Keuper had accepted a position as a senior engineer in RCA’s Systems Analysis section of the Missile Test Project (MTP).

Keuper, a physicist with a Ph.D. from the University of Virginia and a master’s degree from Stanford, had spent the previous five years working for the Remington Arms Company in Bridgeport, Connecticut. In 1957, Keuper visited Jim Stoms in Florida. Stoms, chief engineer for the Martin Company, and Keuper grew up together in Kentucky on the Ohio River sharing their secrets and dreams. After World War II Keuper enrolled in MIT. He finished his undergraduate degree in 1948. During this period he persuaded Stoms who was about to be discharged from the Marine Corps to come to Boston. The two men stayed in contact during the next decade. Stoms encouraged Keuper to leave the Northeast. Exciting things were happening at the Cape. Florida was on the technological frontier. Keuper agreed to have a look. During his visit, Keuper was interviewed for a position with the RCA Missile Test Project.

The interview went well. Dr. Charles Carroll, head of RCA’s Systems Analysis Group, offered Keuper the job of senior engineer at RCA in his section. Keuper returned to Connecticut unconvinced. Fate intervened. On a wintry night Keuper and his wife, Natalie, were driving on an icy New England road. Blowing snow caused Keuper to lose sight of the road. The Keuper’s 1952 MG careened “over a stone wall and landed upside down.” “That did it!” Keuper recalled thinking, ” We’re going to Florida.”

Keuper Gains Experience in College Accreditation at Bridgeport Engineering Institute

During his five years working for Remington Arms in Connecticut, Jerry Keuper served as an instructor evenings at the Bridgeport Engineering Institute (BEI). Initially, he taught calculus. Arthur Keating, BEI’s founder and president, took a liking to the lanky physicist from Kentucky. Keating founded BEI in 1924 to meet the needs of individuals who wished to become engineers but were unable to enroll in a traditional university program. He named Keuper chairman of mathematics department. Keuper remembers discussing with Keating whether to move to Florida. One thing troubled him. He liked teaching and there were no near-by colleges or universities. Keuper asked Keating what he thought of the idea of starting a Florida branch of BEI. “No,” Keating barked, “start your own college.’

Keuper pondered the idea as he prepared to move. BEI was in the midst of preparing its application to Connecticut Department of Higher Education for a license to offer an associate degree in engineering. Keating had charged Keuper with organizing the accreditation process. As a hedge, Keuper made copies of all of the BEI accreditation documents. By the time he reached Melbourne, Keuper decided to follow Keating’s advice. His 1952 MG still had a BEI (Bridgeport Engineering Institute) parking decal on the window. Why not call the school Brevard Engineering Institute?

Four Friends Meet in a Bar + That Famous 37¢

Keuper weighed the possibilities for starting a college during his weeks as chief scientist in RCA’s Systems Analysis Group. The Systems Analysis Group was responsible for assuring the accuracy of the technical data that was supplied by the different sections of the Missile Test Project. The intense nature of the work made for quick friendships. Keuper shared his idea of starting a college with three members of the Systems Analysis team. After work George Peters, a mathematician, Robert Kelly, a computer scientist, and Donya Dixon, another mathematician, would meet Keuper at the Pelican Bar on A1A. Keuper believed that the position of Florida’s aerospace industry was analogous to the northeast’s smokestack industries at the turn-of-the century. A tradition of higher education existed in the Northeast, which supplied a pool of educated technicians and engineers. East central Florida was different. There were no technical and engineering schools near-by.

Peters, Kelly, and Dixon listened as Keuper outlined his plan. BEI would serve as their model. Classes would be offered in the evenings. The faculty would be drawn from the Missile Test Project. ‘Missilemen’ would be the students. The curriculum would be tailored to meet the needs of technicians and engineers who wished to advance. One day a bystander standing off to the side overheard the conversation and tossed thirty-seven cents of change from a long distance phone call on the bar with the quip “go start you college with this.”

Peters, Kelly, and Dixon listened as Keuper outlined his plan. BEI would serve as their model. Classes would be offered in the evenings. The faculty would be drawn from the Missile Test Project. ‘Missilemen’ would be the students. The curriculum would be tailored to meet the needs of technicians and engineers who wished to advance. One day a bystander standing off to the side overheard the conversation and tossed thirty-seven cents of change from a long distance phone call on the bar with the quip “go start you college with this.”

Brevard Engineering Institute grew from these musings at the Pelican Bar. A young inertial guidance engineer named Harold Dibble joined the group in the early spring. Dibble, with a Ph.D. from Cornell and experience teaching in UCLA’s evening engineering program, brought valuable experience to the discussions. Responsibilities were distributed. Keuper was to be the school’s president. Dibble took the title of dean. Peters became the head of the mathematics department. Kelly agreed to serve as the school’s financial officer. Donya Dixon was named the organization’s secretary.

Designing a College IS Rocket Science

Over the next few weeks Keuper and his confederates drafted an outline of Brevard Engineering Institute. The group produced a four-page document, which listed seventeen items. Classes would be held Monday, Wednesday, and Friday evenings between seven and ten. Students could pursue courses in mechanical and electrical engineering and “possibly business administration.” The undergraduate program would lead to an associate degree in three years. BEI would apply for regional accreditation as soon possible. Classes would be limited to “approximately fifteen students”. Admission was open to any individual with a high school diploma. Graduate courses would be added to the curriculum “once the mechanism of the school has been set in motion.” Faculty and administrators would consist of “professional men, regularly employed in local business and industry. In each case, men will be selected to teach in the subject area most related to their regular employment and where their college background shows academic strength.” There would be, however, “no full-time instructors, administrator, or employees (with the possible exception of a registrar).” A Board of Directors would be chosen from local leaders “scientific, industrial, and civic leaders.” Keuper shared responsibility for the school’s day-to-day administration with Dibble, Kelly, Peters, and Dixon.

In the spring, Keuper made his first foray into winning local support for the college. He asked the Brevard Joint Chamber of Commerce to give its endorsement to the school. Norman Lund, Sr., chairman of the Chamber of Commerce, was enthusiastic. Lund had come to Melbourne in 1923 to build U.S. 1. Later he became the business manager for Melbourne Village. Despite Lund’s support, the Chamber gave Keuper a luke-warm reception. They tabled the motion and told Keuper they would give him their decision at their next meeting. Later Keuper learned that the Chamber “had turned down my request and [had] voted to invite the University of Miami to come to Brevard County and set up a similar educational program.” Keuper recalls being “disheartened” by the episode until he learned that the dean of engineering at the University of Miami had rebuffed the Chamber’s overture saying, “Let Keuper do it, he is on the scene and probably can [sic] a better job than we could.”

The Engineer’s “Cotillion”???

Fueled with enthusiasm, Keuper’s “administration” spent April and May working out the details for BEI. The Brevard County Schools agreed rent three classrooms at Eau Gallie Junior High School (now Westshore Junior Senior High School) to BEI. In May the Melbourne Daily Times reported that Keuper and his confederates were organizing an Engineer’s Cotillion, a semi-formal dance, to raise money for the college. The Cotillion would be held on Friday, June 6, 1958 at the Trade Winds Club in Indialantic.

The Engineer’s Cotillion was nearly a disaster. The plan was to have a posh dinner dance complete with orchestra and entertainment. Natalie Keuper and Mary Hayward, formerly a Broadway musical star, would sing. Lilo Williamson agreed to perform Hawaiian dances. A barber shop quartet was added to round out the evening. Louie Camp, the principle of Indialantic Elementary School, served as the evening’s master of ceremonies. Keuper hoped to use the Cotillion to inform the public about the Institute and to raise money for the publication of the BEI’s initial course offering. Tom Doherty, the owner of the Trade Winds Club, catered the event. The evening started on a sour note when Keuper complained about the hors d’oeuvres. Doherty disagreed. The men argued as the guests arrived. Eventually, Keuper “invited Doherty to step outside and settle the matter.” As they were preparing to leave one of the guests whispered to Keuper that Doherty was a champion amateur boxer. Keuper suggested that they move on to the evening’s planned entertainment.

The Cotillion raised enough money to print a catalog for the fall semester. A few days later Harold Dibble announced that registration for classes would be held at the Country Club college office of the University of Melbourne. A secretary would take registrations Monday through Friday from nine until one. Registering students presented Keuper with a surprise. The would-be students made it clear that they did not want to attend an “institute.” They wanted to go to college. Keuper agreed and overnight BEI became BEC (Brevard Engineering College). With a razor he removed the “I” from the BEI parking decal and pasted in a “C.” All great universities have parking decals. BEC was off to a great start.

Our First Course Schedule

The course catalog appeared in July. Nine classes were listed. They included:

- Advanced Calculus

- Transients in Linear Systems

- Statistics and Probability Theory I

- Modern Algebra

- Advanced Circuitry Analysis

- Servomechanisms

- Electromagnetic Fields

- Transistor Theory I

- Numerical Analysis

Tuition for one course was $35; $68 for two; and $96 for three. Classes were scheduled to begin on September 22. Moreover, Dibble announced that the school intended to offer graduate courses leading to a master’s degree in electrical engineering and applied mathematics. Dibble explained that the “basic philosophy of the graduate division” of BEC was to offer courses which were designed around the special expertise of the individuals working at the Cape. “The men who are doing the teaching,” Keuper added, “are practicing what they teach in the day time.” He cited as an example of this a course on rocket propulsion taught by Sebastian J. D’Alli. D”Alli, a member of a local engineering firm, had extensive knowledge of rocket engines. BEC’s course was designed to take advantage of D’Alli’s unique experience.

MIT Understood Our Vision and Lends a Helping Hand

Alten Thresher, who served as Dean of Admissions at MIT, gave BEC an unexpected boost. Keuper had met Dean Thresher during his undergraduate years at MIT. Earlier in the summer, Keuper had written to Thresher outlining his plan to model BEC on Bridgeport Engineering Institute. “I have always felt,” Dean Thresher replied, “that the Bridgeport [Conn.} Engineering Institute represented a very sound and viable educational effort, and it is good to know that the pattern is now being reproduced in Florida. We are entirely willing to consider for possible credit here subjects given at Brevard which are substantially equivalent in content.” Thresher had visited Melbourne in 1957 and knew about the educational “problems in that area.” Brevard Engineering College, Thresher concluded “seems to be an excellent solution to some of them.”

The First Faculty Meeting

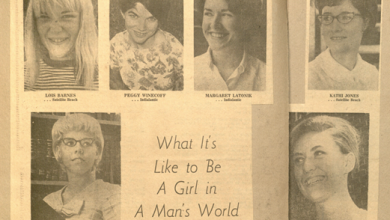

By early September 154 students had registered for classes. There were 114 undergraduate and 40 graduate applicants. The average age of the applicants was thirty-three. Six women were among the first students. These figures were announced at BEC’s first faculty meeting which was held at Hensel’s Red Rooster Restaurant in Eau Gallie on September 18. Forty-five prospective faculty members attended the dinner meeting. Keuper explained to the group that the purpose of BEC was to “train men and women who might not otherwise gain such an education in engineering, the sciences, and business administration.”

The rest of the first faculty meeting consisted of Dean Dibble and the school’s treasurer, Robert Kelly, described school’s procedures. Dibble outlined the teaching assignments, how tests were to be administered, and his own philosophy of teaching. Kelly summarized the school’s financial situation and told the faculty that an agreement had been reached with the National Bank of Cocoa to help students finance their tuition.

The next night a “mass meeting” of the students and faculty of BEC was held at 7:00 PM at Eau Gallie Junior High School. Students purchased their books and course materials in the school’s foyer. George Peters chaired the meeting. When Peters introduced Keuper as the school’s president one student called out, “Hey, he is the guy who sold me the pencils.” Selling pencils was simple. Arranging with publishers to ship books was more difficult. One of the publishers sent their books C.O.D. to the Eau Gallie post office. Keuper and Kelly managed the book sale in such a way that they were able to “collect enough money from the sale of other books to bail out the rest of them.”

The Missilemen Go to College

Money was to remain a perennial problem. There was, however, no shortage of enthusiasm. BEC’s first students and faculty were hard workers. “I’ve only been fishing once in the last five weeks,” Missileman Arthur Penfield reported. “I haven’t got time…and I’m a rabid fisherman.” Penfield was a typical BEC student. Penfield, a forty-year old retired Navy chief warrant officer, worked at the Cape as a computer specialist. The navy trained him to be a technician “who can get by” on what he knows. He wanted, however, to be an engineer. BEC gave him an opportunity for advancement.

Money was to remain a perennial problem. There was, however, no shortage of enthusiasm. BEC’s first students and faculty were hard workers. “I’ve only been fishing once in the last five weeks,” Missileman Arthur Penfield reported. “I haven’t got time…and I’m a rabid fisherman.” Penfield was a typical BEC student. Penfield, a forty-year old retired Navy chief warrant officer, worked at the Cape as a computer specialist. The navy trained him to be a technician “who can get by” on what he knows. He wanted, however, to be an engineer. BEC gave him an opportunity for advancement.

This was the same reason that Glenn Routh, a thirty-two year old Boeing technician working on the Bomarc missile, was going back to school. BEC was his last chance to become an engineer. RCA and the other base contractors faced the constant threat of losing their best technicians because of the lack of educational opportunities. “Engineers like to continue studying,” John Wright observed. “That’s why places like Boston with MIT, and Chicago and Los Angeles are so appealing. Brevard College will help us keep engineers in the area.” At the Cape, Wright led a team of twelve engineers charged with devising firing mechanisms. Wright enrolled in BEC to earn a degree in space technology.

Five weeks into the first semester the faculty met at the Red Rooster Restaurant to compare notes on their classes. “I’ve never seen students slave like this,” one faculty member observed. Eight of the twenty-three faculty members held Ph.Ds. Like their students, most of the faculty were employed by private contractors at the Cape. Keuper and Dibble had recruited seventy-five students from their fellow RCA workers. Additional students came from contractors such as General Electric, Aerojet, Convair, and Radiation, Inc.

National Recognition for “Countdown College”

Midway into its first semester BEC won national recognition when both Newsweek and Time Magazines sent reporters to cover the college. Newsweek praised the determination of both the faculty and students. “While technicians at Cape Canaveral prepared for the Army’s first attempt to raise a rocket to the moon,” the Newsweek reporter declared, “a project to raise the educational level of the base’s personnel moved smoothly into orbit last week.” Ad Astra per scientia.

*Both men and women working at the Missile Test Project were called “Missilemen.”

Video of Original Explore 1 Launch in 1958