Capitol Briefing

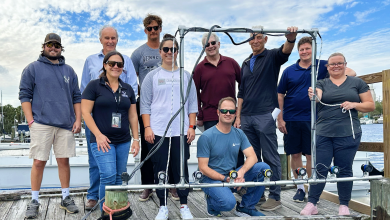

(Remains at the Jersey shore after Hurricane Sandy)

In the wake of Superstorm Sandy, it was Harry Friebel’s job to assess the effectiveness of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ coastal protection projects … and share that work with Washington.

Vice President Joe Biden wanted to see the destruction for himself. Last November, he stood on what remained of the boardwalk in Seaside Heights, a New Jersey resort town that had previously been best-known as the summertime home of MTV reality stars Snooki and The Situation.

That image changed in the days following Hurricane Sandy, the superstorm that touched down on Oct. 29, claiming at least 159 lives and causing upwards of $50 billion in damage across the Northeast coastline. Dressed in a leather bomber jacket and khakis with a Seaside Heights Police baseball cap, Biden stood a few feet from a tangle of roller coaster tracks that ended up in the ocean—a sight that became one of the iconic images of Sandy’s aftermath. Biden, the former Delaware governor who spent years vacationing at the Jersey Shore, assured the storm’s survivors that he understood what they needed to rebuild their lives. “You’ve got a homeboy,” he said of himself, “who gets it.”

One of the people flanking Biden that day who helped him understand Sandy’s impact was a fellow Garden State homeboy—Harry Friebel ’97, ’00 M.S., a coastal engineer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who spent the day with Biden as he met with first responders and toured the beach.

“He asked very intuitive questions,” Friebel says from his office in the historic Wanamaker building, overlooking downtown Philadelphia. “You could tell he’s not one of those people thinking about what he’s going to do two hours from now. He was in the moment and listening. It wasn’t a publicity stunt.”

Friebel’s path to the Corps and his day with the vice president began in the ocean. The 39-year-old South Jersey native started surfing in grade school, never thinking his love of the sport would lead to a career. A lecture from a coastal engineer during his freshman year at Florida Tech was a revelation. “I thought, you could get paid for this?” he says with a laugh. “Teachers say that surfers have a lot of intuition to grasp the subject. You’re out in the water, you know how the currents move, where the waves break. So when you’re in the classroom, it’s easy to visualize. It was a match made in heaven.”

Simply put, Friebel’s job with the Corps is “dune builder,” and his regional office oversees federally funded beachfront preservation projects in the lower half of New Jersey and all of Delaware. None of them had faced a true test from Mother Nature until this storm, and fortunately, the four islands Friebel oversees were spared much of Sandy’s wrath. A tour of the coastline in a Blackhawk helicopter in the days afterward proved the Corps’ dunes “passed with flying colors,” he says. “The eye-opening thing for me was the difference in the damage where we had a project and five blocks away where there was none. It was night and day.”

A few weeks later, as Friebel and his teams were busy assessing beach erosion and drawing up plans for repairs, he received a call at home on a Saturday morning—Biden was visiting New Jersey the next day and the Corps wanted Friebel to help brief him. The vice president’s entourage arrived by helicopter and met with state and federal officials for a closed-door session at a Seaside Heights fire hall, where Biden threw the engineer into the conversation, literally. “I was actually hanging in the back and he was talking to the higher-ups with FEMA,” Friebel recalls. “Somebody said ‘There’s a guy from the Corps here.’ And he reached behind, grabbed me by the shoulder and literally pushed me to the table.”

During that meeting and a walk along the beach, Biden asked Friebel practical questions about the dynamics of beach erosion and the dunes built by the Corps (Seaside Heights is one of a number of New Jersey shore towns that isn’t working with the Corps, either due to issues of funding, permission from land owners for construction, or both). When Biden asked if Seaside Heights would have suffered such catastrophic losses if the Corps had built dunes or a seawall there, Friebel told him bluntly, no. “We weren’t trying to sell anything to him,” Friebel says. “If he had a question, we wanted to answer it.” The engineer’s words seemed to make an impact. When Biden spoke to the press that day, he called for more funding for the Corps.

By 4 p.m. that afternoon, Biden had flown off to the New York area for more damage assessment and Friebel was on his way back home, ready to attack the less-glamorous task of repairing the eroded dunes from Long Beach Island to Avalon and Atlantic City—many of the same beaches he’d surfed as a kid. For Friebel, the experience confirmed that his work with the Corps has the potential to save both property and lives along the coastline.

With hurricane season starting up again in June, Friebel hopes that his new pal in the White House continues to carry that message. “I hope we won’t have to go through something like this again,” he says. “But I’m sure we will.”

Story by Richard Rys