Genetics Show There’s No Place Like Home for Shark Births

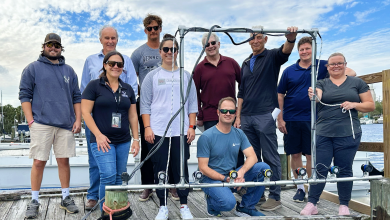

Throughout her work, Florida Tech Ocean Engineering and Marine Sciences assistant professor Toby Daly-Engel has used genetics has used genetics to uncover hidden diversity in sharks, including the discovery of new species and using sharks’ hereditary makeup to understand how they use coastal habitat to protect their young.

That research is spotlighted in “Shark Family Tree,” a new episode of the Breakthrough documentary series now available on the streaming service Curiosity Stream.

The Breakthrough series take an in-depth look at recent developments in the sciences, focusing on stories that have an impact on our understanding of the natural world and the universe at large. Curiosity Stream, a streaming-video-on-demand outlet launched in 2015 by Discovery Communications founder John Hendricks, contains a deep lineup of more than 2,400 documentaries and other factual content exploring science, nature, history, technology, society, and lifestyle.

According to Daly-Engel, in order to study great white sharks, traditionally one catches them and attaches a tag, allowing researchers to follow them. However, with genetics, in addition to (or sometimes instead of) tagging, researchers are able to collect a tiny sample of shark tissue, which can provide information to compare it to other great whites around the world. Using DNA analysis together with tagging can lead to a better understanding of the multi-generational connections and birthing habitats of sharks, which can in turn help conservation efforts.

In her research, Daly-Engel examined two different populations of great white sharks, working with a local team to tag and get samples from approximately 56 sharks. In coordination with the demographic data, they were able to identify siblings and their familial connections.

“We wouldn’t expect these animals to hang together, even if they are related” Daly-Engel said. “They tend to compete with each other, and we haven’t noticed any kind of previous behavior that would suggest cooperation. Sharks in general don’t socialize much, because they tend to either compete for prey or eat one another.”

While the research didn’t link the two populations to one another, the work looking at the two groups allowed the team to build a pedigree of the sharks and how they were related, helping the researchers to get a better understanding of their natal homing habits, which is when an animal returns to its birthplace in order to reproduce. The information also provided some clarity on the importance of coastal habitats for sharks and the feeding aggregation of marine mammals offshore, such as Isla Guadalupe, Mexico.

“That’s an adult habitat, there’s no nursery habitat, but you’ll get young sharks showing up there and then we find their parents in the same spot,” Daly-Engel said. “So, we have these multi-generational connections at these offshore feeding sites full of tasty seals, meaning the site must be really important to the life cycle of that animal and probably has been for a long time, since they can live for close to 100 years.”

Through looking at the genetic makeup of great white sharks, Daly-Engel is seeing there is no place like home for bringing new life into the world.

“There is an inhibition to movement in these sharks,” she said. “They’re the biggest sharks, they could disperse across the entire globe, but genetics has told us that not only are they staying sometimes close to home, but even if they’re ranging, they’re coming back to the same spots to reproduce. Not only that, but we know they’ve been doing it for tens to hundreds of thousands of years, because we can see it in their DNA.”

A preview of “Shark Family Tree” is available here.

Click here to support Shark Conservation Research at Florida Tech.

###