Listening to the Lagoon: What its Creatures Can Tell Us About its Health

Barnacles and other marine animals serve as Indian River Lagoon sentinels

Last spring, research assistant Kody Lieberman pulled a set of framed PVC panels from beneath the Indian River Lagoon.

“Historically, we get a lot of barnacles at this site,” Lieberman said.

Lieberman works at the Center for Corrosion and Biofouling Control at Florida Institute of Technology run by Professor Geoffrey Swain. The center is funded by the Office of Naval Research and Industry to develop environmentally friendly coatings and methods to prevent barnacles and other unwanted marine organisms from developing on ship hulls and other structures.

Though this particular panel pulled from the water looked like it had a lot of organisms like barnacles and sponges clinging to it, in recent years Lieberman and his research peers have noticed worrisome periods of decline. “Recently, the number of barnacles have fluctuated,” said Lieberman, “and this appears to be associated with the changing health of the lagoon.”

The researchers have seen a marked decline in the amount of marine life at the test site. It seems Mother Nature, fueled by man-made development and other impacts, has lost her vigor, leaving a wounded lagoon.

Although the full impact on the summer-breeding barnacle population is still unfolding, decline in barnacles and other filter-feeding organisms is not good for the lagoon, Lieberman said.

They and other marine animals in the Indian River Lagoon are sentinels of the ecosystem’s health, a unique and important indicator of how the community is doing as custodians of this valuable body of water.

The data gathered by Lieberman at the test site compliments the technology and research of others at Florida Tech to help lead to better understand and management of the lagoon.

Jon Shenker, a Florida Tech biologist, has seen the estuary’s troubles affect the number and diversity of the fish that have called the lagoon home and that he studies. Algal blooms deplete the water of oxygen, causing fish to suffocate and die.

And just one event like a fish kill has implications for all living organisms in the lagoon. “Those fish won’t produce new fish to replace them, and that has an impact,” Shenker said. Dolphins rely on fish for food and are territorial in their habitat, without enough fish the dolphin population will likely decline, too.

But as is often the case with the natural world, its denizens can help repair the damage in addition to falling victim to it.

Years ago, for example, the Indian River Lagoon teemed with oysters. But scientists say that over the years pollution and coastal construction such as bridges and seawalls have wiped out huge numbers of them. One important step to stemming the lagoon’s decline, said Robert Weaver, an ocean engineer at Florida Tech, is to restore the oyster population in the lagoon.

Oysters are considered to be important to the lagoon’s health for a number of reasons: other species depend on them for food and habitat; large clumps of them create natural reefs that help block wave energy, which prevents shoreline erosion; and they filter impurities from the water.

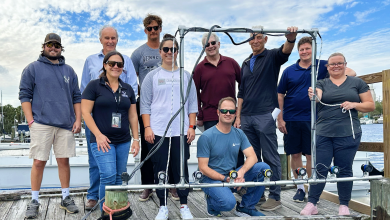

Weaver and Kelli Hunsucker, a research assistant professor in the Department of Ocean Engineering and Sciences, started Living Docks, a program aimed at enlisting the community’s help to turn docks and seawalls along the shores of the lagoon into a home for oysters. The program enables non-scientists and community members to create inexpensive but effective habitats that encourage oysters and other organisms such as sponges and barnacles to collect near man-made structures in the lagoon.

Mesh bags filled with oyster shells are by hung from the sides of these structures and submerged into the water. The presence of the shells attract oyster larva and other filter-feeding organisms.

“One dock with 37 pilings with an average of 32 oysters per piling can potentially filter about 21 million gallons of water per year,” Hunsucker said, not including the filtering impact of other organisms, such as barnacles and sea squirts.

Weaver is also working with students, faculty and community volunteers on a Living Shoreline project, which uses oyster beds near the shoreline to act as a breakwater and native grasses and mangroves planted on the banks to buffer erosion. State funding for the initiative was secured by Jody Palmer, a 2007 graduate of Florida Tech now serving as director of conservation at the Brevard Zoo. The zoo is a leading partner in the project. Improved shorelines.

Earlier this year, Weaver and his team had started surveying a section of the Indian River Lagoon on the north side of the Melbourne Causeway. The plan is to model the breakwater in the lab using a wave machine and then implement it into the lagoon.

“We are trying to give people real ways to help the lagoon, something to feel good about – something they can do on their own property,” Weaver said. “Whether you have a seawall, revetment or natural shoreline, there are ways to contribute.”

Back at the bio-fouling research lab a few month later, summer barnacle breeding is underway. Lieberman wasn’t overjoyed at what he was seeing, but he was encouraged. The lagoon is resilient, even in its delicate state.

“We have had fewer barnacles than 2015 so far,” he said. “However, we still had more barnacle recruitment than the years right after the algal superbloom, and the season is not over. I am staying optimistic.”

%CODE1DISCOVERYMAGVOL13%