Upward Lightning Findings Vital in Structure Protection

As major cities around the world grow and add new buildings to their infrastructure, understanding how lightning might affect those towering structures is increasingly important.

New findings from a study on upward lightning are providing Florida Institute of Technology researchers critical knowledge that is expected to lead to improved lightning protection of tall buildings and other structures.

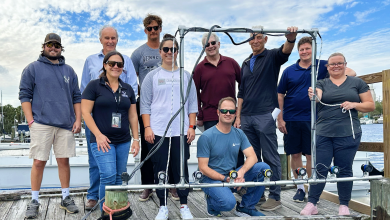

The study was the result of an international collaboration led by Amitabh Nag, assistant professor of aerospace, physics and space sciences at Florida Tech, along with two others from the Melbourne university – Ph.D. student Naomi Watanabe and Hamid Rassoul, Distinguished University Professor of Physics. The results were published in the paper “Characteristics of Currents in Upward Lightning Flashes Initiated from the Gaisberg Tower” in the journal IEEE Transactions on Electromagnetic Compatibility, on which Watanabe served as first author.

Researchers from the Austrian Lightning Detection and Information System and the University of Florida also made significant contributions to this study, which examined the characteristics of lightning observed at the 330-foot-tall Gaisberg Tower in Salzburg, Austria, from 2000 to 2018.

According to Nag, upward lightning differs from its downward counterpart as it starts with a long-duration, low-level electric current from an object on the ground, while downward lightning moves down from thunderclouds and produces more impulsive currents when it touches ground. Upward lightning mostly occurs from grounded objects taller than 100 meters (about 328 feet), such as buildings, wind turbines and communication towers. It can also be initiated by a spacecraft that is taking off. Upward lightning is of special interest in the Great Plains area of the central United States, which has both frequent lightning storms and wind farms, as well as the west coast of Japan, where low-hanging clouds in the winter can produce powerful upward discharges.

“The different nature of upward lightning is what makes us want to understand it better, which can lead to improved equipment design, or better lightning protection standards for tall objects,” Nag said.

Prior to development of tall structures in lightning-rich cities, upward lightning was not as common as researchers are discovering today, according to Nag.

“As the tall infrastructure grows, the chances of the buildings initiating upward lightning increases, and that’s why it is of direct engineering interest,” he said.

After such research findings are published and summarized, CIGRE, a standardizing body of science, and ultimately the International Electrotechnical Commission, may produce updated scientific and engineering standards from such work, and this may lead to the building industry developing new codes of compliance.

While Nag doesn’t see upward lightning leading to decisions to lower the heights of newly constructed buildings, research such as the work being done at Florida Tech could ultimately lead to safer buildings and infrastructure.

“It’s not that we will change how tall our buildings will be,” he said. “We’ll just be able to protect them better from lightning.”

###